The Bourbon Hospice for the Poor and the history of Neapolitan Artistic Handicraft

“PALAZZO FUGA”- the historical enclave of the TOWN CRAFTS

The construction of the Bourbon Hospice for the Poor started in 1751, but came to a halt and then restarted in 1826. This building is a former public hospital designed by the architect Ferdinando Fuga outside the Aragonese walls.

The king Charles VII of Bourbon in 1749, within his renovation plan of the city, called Ferdinando Fuga to design the Hospice for the poor, which should have been a shelter for the mass of poor people in the Reign.

The building was originally designed with five courtyards and a church in the centre, entered through the central arch, but only the three innermost courtyards were built, and plans to complete the building according to the original design were finally abandoned in 1819

In the first half of the XVIII century, Naples was marked by a large scale renovation of the Minister Berardo Tanucci, who signed the decrees on the abolition of feudalism and clergy privileges, one of the 1st ever passed by the Neapolitan Enlightened thinkers, such as Genovesi and Galiani.

At the time the project remained unfinished, in fact, today’s facility is only one fifth of the original plan. The reasons were lack of money and a change in priorities after the death of Charles VII. His son Ferdinand IV decided to allocate only part of the structure to housing and the rest to manufacturing.

This monumental building, whose façade is on “Carlo III” square, represents an historical place where key events have taken place for about two and a half centuries. The documents found there provided an invaluable means to understand the history, the political choices and the social structure of the town.

This building was originally meant to host about 8,000 poor people, dividing them by age and sex.

The ratio behind this kind of planning was that the daily flux of incoming poor, would be better monitored and the guests would be better trained and employed for community service.

The initial ethic and social aim of this massive structure was to act as a catalyst for human resources that needed to be transformed from a burden for the reign into an invaluable work force.

Unfortunately, the tragic events of 1799, which forced the king to flee to Palermo on a ship and the break out of the civil war, abridged Fuga’s original design.

The king and the government dismissed the original design and approved a more

cost-effective plan by the architect Maresca, who replaced Vanvitelli in the supervision of the work. The space immediately available was used as workshops for convicts.

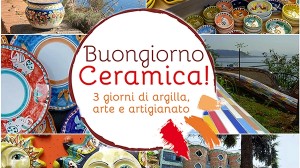

What emerged from the documents found onsite is that the Hospice has trained a number of young craftsmen, who formed the basis for refined handicraft business still present in Campania nowadays.

We need to keep in mind that the potential of handicraft and old crafts in historical towns is a wealth and a resource to be valued and preserved.

The Hospice of the Poor was to become a “craft centre for the Town within the Walls. In fact, during the reign of Ferdinand II the facility was called: “the Great Emporium” as if to confirm its key role during the industrialization period of the reign. It also had a central role in the social and economic life of the Bourbon Capital.

After the Neapolitan Republic, Ferdinand II liberalized the businesses passing bills, signing agreements and giving some bonus to the entrepreneurs. The Hospice of the Poor represented the heart of all crafts and many youn craftsmen started their apprenticeship there under the supervision of the King.

Under the French reign too, Industry expanded and new technologies and machines where used. Following the Council of King Ferdinand, another Council was appointed to follow the production process of handicraft in the Reign to perfect and expand it. Among the first initiatives there was the publication of a technical, scientific and commercial newspaper.

The Hospice had a traditional crafting system, but it was a place of great innovation, in fact, during the restoration there would be the introduction of the mechanic frame Jaquard, which revolutioned the traditional hand work system.

Textile activities in the Bourbon Kingdom have always had a paramount importance in the economic structure, although in England and France there were more industrialized and advanced technologies, which boosted the fashion sector.

During the reign of Ferdinand II, the research and development of new technologies, thanks to the Art Board, the royal support and the Exhibits, was pushed to the limit.

In addition, the role of the Hospice, was marked by the synergy between the training of young people, the craftsmen and the new machinery that had been introduced.

This is when the prestigious coral manufacturing of Paolo Bartolomeo Martin, form Marsille, took over the production and the training of young convicts: the documents of that age report a great flourishing in artisans, even more gifted that the school in Torre del Greco (also founded by Martin).

Inside the Hospice there was also a wool mill which produced military clothes and it involved about three hundred convicts and a lot of blind kids worked the wool.

According to the documentation, the “Correctional Facility” was also involved in different activities like dying, producing nails and toil (Macmen method), fixing shoes (Aldostro), working the wood (Filippo).

The restoration and conservation of this historical place of Naples has to keep into account the history of the crafting culture of the Building, so that the proud history and the vibrant traditional “Handicrafts of the town” can be preserved and promoted all over the world.