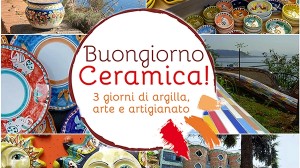

The porcelain made in Capodimonte, which takes its name from the hill on which it is produced, is among the best examples of artistic handicraft representing Neapolitan culture and history all over the world.

Capodimonte porcelain is linked to the history of the Bourbon dynasty, in fact, in 1743 the factory was founded in Capodimonte Royal Palace, residence of the King Charles of Bourbon and his wife Anne of Saxony. Over time the artistic production of Capodimonte has become more valuable and more famous than the French and the German ones.

The reason why King Charles and his wife founded the Royal Factory of Capodimonte was to create artistic products more precious than the ones made by the German factory’s in Meissen.

The special feature of the ceramic dough produced in the Royal Factory of Capodimonte is its “suppleness”.

In fact, unlike factories in Northern Europe, the dough production in the South was the result of various types of clays (coming from the Southern quarries) mixed with feldspar (which has no kaolin). The resulting mixture is unique because it is supple and pale.

This soft-paste allows the manufacturing of miniatures that are real art works and are processed by brush tip.

In 1700 the sculptor G. Ricci, the chemist Livio Vittorio Scherps, and the decorator Giovanni Caselli refined the composition of the mix, improving its quality. Caselli created Queen Amalia’s famous parlour, which is considered the highest expression of plastic and pictorial skill of Capodimonte artists of the time.

The last two decades of the 18th century are regarded as the period of greatest magnificence for the Royal Factory of Capodimonte since Domenico Venuti became its artistic director and founded a real school of art which produced beautiful tableware and precious vases, now in the Museum of Capodimonte Collection.

As a consequence of the French domination in 1806, the factory was sold to a group of private individuals who accepted to hire all the workers of the factory in return for orders placed by French kings.

But, since Domenico Murat had to subsidise Napoleon’s very expensive military campaigns, he did not honour the commitment and stopped any support to the production of the Capodimonte porcelain.

This did not prevent Neapolitan artists from inventing new styles and producing extremely valuable porcelains that were soon appreciated by Neapolitan middle-class and by tourists.

Nowadays the Royal Factory of Capodimonte, in Naples, has been turned into a museum where the most famous artefacts of the Neapolitan tradition are stored and admired. Besides, Capodimonte porcelain represents an example of excellent handicraft all over the world and its artistic products are still crafted by expert hands.